Critical references

Ioan Aurel Mureşan on the Silk Road

Ramona Novicov

”The game seems simple: the painter Ioan Aurel Mureșan stages a fiction, calls his character the “Duke d’Ivry”, and distributes himself in the role of “court painter” at his service.

But what kind of a fiction is this and who is the character chosen or destined to grant his author the noble title? What exactly covers up the transparent substitution Author/Narrator/Character? It’s true that the Bovarysme “le duc c’est moi!” is staged with a tacit complicity, but a secondary text, this time Rimbaudian, permeates subversively the sumptuous fabric, to tell a different story, that is “Je est un autre”. Only now an entry passage is opened to the ultra-marine world of the duke: more than a double, we find somewhere, in the depths of the painting, a deviation from the norms of grammar and visual rhetoric. The incongruity of the phrasing, its hiatus, points to a fracture somewhere along the axis Author/Narrator/Character, an euphemism for its grandiose staging.

But Ioan Aurel Mureșan knows too well the rules of the game with the image, he knows what a splendid and dangerous camouflage the painted canvas can be; as it does not merely hold the projection of an entire fictional universe, but, in addition, it carries the tension of the intersection between this highly personalized, authorial universe and the nothingness behind it; from passive screen it becomes an interface, a plastic, pulsating diagram able to stand the pression of the collision of the two worlds: the one before and the one behind the painting. And yet, how are we to know where the point is up to which the painted canvas (fragile convention) is just a curtain, a camouflage, an alibi, a subterfuge, a substitute, a tool of seduction... and where it becomes real, that is not beautiful or ugly, but true, a piece of evidence and a pledge for the indubitable, unique, and necessary existence of a certain painter called now Ioan Aurel Mureșan?

We know that the answer to these introductory questions is embedded in the painterly matter. We know that the painting itself is stratified and boundless writing that contains all the questions and all the answers that Ioan Aurel Mureșan, willingly or not, has planted in the field of the image from the abundance of his culture and sensibility.

What justifies then the commentary of a story that already has a narrator, a story that seems, at times, autogenous and which, at the climax of its narrative fervor, tends to occasionally outrun its own creator? If the “initiative of the image” has the power to reverse the relation creator-creation, then the storyteller could be the one that becomes narrated, that is assimilated, intertwined, swallowed by the narrative flow – and, sometimes, even created by it. Here, in these dangerous waters, a metonymy par excellence, we could find the plausible justification for what follows, entitled

The Silk Road

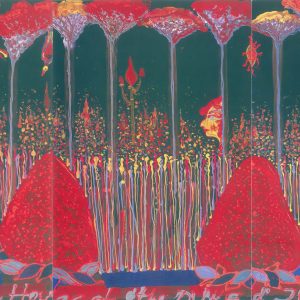

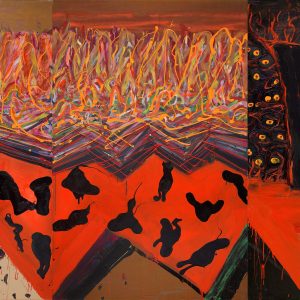

The Wonderful Travel of Duke d’Ivry is a confirmation that an adventure begins at the very moment when exasperation and exaltation coincide. The mix is incendiary, amplifying in the splendor of the hours the calling of the ultra-marine shores of the Levant. The duke knew that it was there, across, that he will find the gold of the big cats, of the nights when he did not dream, he did not love, he did not believe in anything, of “one thousand and one nights” that harbor in their depths a storyteller wrapped in silks waiting for him. Therefore, no matter how dangerous it might be, the road to her remains the Silk Road. Because he is not the wandering knight, pure and phantasmagoric, but the heroic explorer, Marco Polo. He knows where he is coming from, he has a “home”, he knows how many literary texts and visual quotations are plaited in the The Silk Road or in Scheherazade’s braid, he knows how to sneak in, like a chameleon, in her palace through the nets of the chromatic fabric and how to amplify the fineness of the stroke or how to deconstruct the efflorescence of the duct of the gesture. And precisely because he knows all these, he deliberately leaves behind the alcove of the wonderful hours and assumes the risks of escaping from them and from everything that is defining, protecting, comforting, making him happy. He must leave, and the adventure he lets himself lured by presents itself as a play of seduction and alterity; because, in this existential fracture, “Je est un autre”. The emblem of this travel could be the double volute, a geminated visual syntagm, interiorized, speculative, a good camouflage for a heraldic key-image we could call Ivry Bifrons, with the entire adjacent cortege of double games – conditioning, competition, obstruction, substitution, usurpation, interference, jamming, blockage, complicity. The simultaneous contrast is, at the limit, suicidal.

The travel has become anyway inevitable, as it is necessary; only by making it the access to a new initiating stage can be reached. The painted image condenses the customs and dangers along the road: temptations, disguises, abandonments, moments of bliss.

But what is the sense invested in all this demonstration of forces?

A Borgesian answer seems very tantalizing: “only to have a drawing!” But a drawing that contains the whole world, from beginnings till the end, one that can only be kept hidden, for example in the infinite net of the arabesques or in the depths of a story or in the living fur of the jaguar or… anyway, in an indestructible language, one of a wonderful gratuity and evidence – there the secret of the “writing of the god” is kept. And the Duke d’Ivry knows, as he can sense the cipher of this magical writing in the main fabric, that this is what he has been looking for in the search for the Holy Grail or Sindbad’s treasure, reinventing the Persian stories, the legends of the Knights of the Round Table or ambiguous personal mythologies; or maybe he is not looking for, maybe he lets himself being looked for, maybe he is the one who abandons himself to the entrelacsto their dangerous embracement. Lacs d’amourAs if a bundle of keys is scattered on the surface of a Persian rug. One door after another opens, threshold after threshold, warm, cold, warm, warm, hot, the room of secrets is here, at the center of the arabesque maze – and? is this not enough? The wonderful dizziness that gave the name to the duke is not a satisfactory reward per se? is this not the prize for his magical travel? it could be, but it is not. Because the duke is fundamentally a dual, cleft, conflicting character. As much seduction/as much solitude, as much victory/as much solitude, as much voluptuousness/as much solitude. So much solitude!

Let’s focus on this cleavage: “Je est un autre”. Je n’est pas moi. And why can he not be? because the interior crevice turns the duke into an “abyssal” character. He misses, simultaneously, both the West and the Est, the “Garden of Delights” and that of the Olive Trees, the “cologne and delicatessen”, but also the “Promised Land”. Bi-location, this simultaneous abrupt contrast, indicates the existence of a split in the axis of the being, the so much feared abyssos.

But this is not the only one. There is there, as an underlying sign of the ducal adventures, a one more beyond, an ultra-space: the ultra-marine abyss, the absolute vertical horizon. The call of the Indies, of the artificial paradise is fueled by the aquatic fascination which the duke, as his court painter confesses, feels intensely. And the sign of this fascination can be none other than the single invariant of all the images of the travel: the winding path. Everything is tangential to this vibration, to this immemorial, infinite respiration. Here it is, at the foundation of images, in the planning of their birth, pulsatile diaphragm whose pitching involves practicing a passage ritual. We are entering a new territory; we are following a new script. Its composition is fixed: the triptych. Three is a privileged number and, in addition, it dissolves the double. But the succession of images is not one, two, three but three, one, two. The beginning is the end. At first, we are being shown the ending of the adventurous episode, following what and how has happened. Thus, the temporal sequences get, by reversal, a cyclic form; and it is so because the duke senses, or maybe he already knows, that the adventure predates him. Like a poem with fixed form, a gazel, for example, the story experienced by the duke has been told, woven, lived before, and the beings that populate it have been transformed into words. Or in colored stalks. Each image with the duke is nothing but its recalling. Three, two, one, the snake bites its tail. The visual space becomes recurrent, contained, inexorably cyclic. The wheel of the world throws him back in the game, dice in the hand of a Persian princess. Or maybe king on her chessboard?

The duke’s adventure is protected by a winding thread of silk. Seen from above, among the palaces and poems, it looks like a supple drawing on the checkerboard of the Eastern empires. A delicate and persistent drawing, able to survive even after the empires have been dissipated in other poems and fabrics.

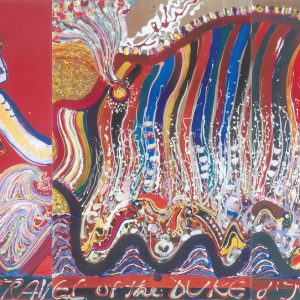

We change the perspective, diving into the image. We choose as first moment of the assault the episode of the duke’s re-birth. Expelled from the mouth of Jonah’s whale as its first utterance, the duke erotically/heroically enters the worlds naked, thirsty, and perplexed. The baptism by water (waves, tears, veils, clouds) and by fire (vivid red, the hot skin of the painting, gold, purple) makes the duke a porphyrogenitus! This round, final moment of the epiphany opens up retrospectively to ahow was it posisble Here is how”: the court painter also takes his role, and nothing seems too much to him to demonstrate his storytelling skills. From chansons de geste to epithalamium, every tonality seems right. Now the images depict the duke as a ripe fruit in the belly of the whale: whirling, inseminations, and ecstatic deaths, transmutations, babblings, opus magnum, silkworms. Luz, blue citadel, the foam of your immortality is carried by now on the garments of Duke d’Ivry – would probably say a minstrel.

Another episode, the contemplative one: in the golden rain, under the transparent shade of the palm tree, in front of his demonic face, of the “other” Ivry, the duke stays quiet. Totally detached, he contemplates the play of the opposites; he looks across the barren precipice of the chalk ridges. He is far away from the funerary procession, he doesn’t see any more the crown jewel from the country of the shadows, the purple chariot; he is also far away from the hell’s gate packed with skulls. He is no longer chained by crazy virgins either, flames over the ashes of some foreign treasures. From an axial perspective, he stands on the edge of nothingness, reclining on the border of the frame. The “Silk Road” is winding meanderingly and endlessly while he stands upright, unruffled, still. It’s his moment of illumination when, under the shade of a palm tree, he himself has turned into a golden rain.

Another moment is that of the vision of the Great Wheel of the world that suppresses any duality. Everything is already inscribed there, “all that is as it is, all that isn’t as it isn’t”, only the writing is encrypted. The duke can only read it by bathing in the flow of its manifestation, remaining, in the height of the battle, in the saddle of the blue gryphon. From above, from a cosmological perspective, the duke comes down abruptly in the world by means of a powerful raccourci; suddenly touched by a coup-de- foudre, we see him prancing in front of a radiant purple mandorla. But the duke has already crossed its hot threshold and we know this as the entire imagine is now lit by the black sun. It’s the sun that the missionaries see when they are blinded by the flash of a revelation; it’s the sun seen from the inside of the world, as pure immanence. And, in the space of a vision, the eclipse invests the painting with a radiant glow; how? by suppressing the shadows. There is no chiaroscuro anymore, everything is happening outre-mer: pure glow, gold, and blinding azure. outre-mer: strălucire pură, aur şi azur orbitor.

In another triptych (let’s call it Fitzcarraldo), all the gardens in which the duke has relished now look like a jungle, a paradise that has lost its innocence. The comfortable order and clarity of the garden is now invaded by gigantic vegetation because the duke wishes to dive into it, to hide and rest in its vegetable alcove. Now everything has become not only wonderful to be looked at, but also wonderful to be tasted. Among cactuses, cauliflower fungi and, above all, giant strawberries, he wants this world to welcome him into its warm bosom – and only then he turns into a violet, melancholic and heavy, wild, and sad bison.

The Kagemusha triptych: the moment has come for returning home from a foreign land; reconcentration, reunion. The sway of duality has vanished, the duke has reabsorbed his shadow, his lookalike, he has found himself as One. He has overcome him dual condition only when he was able to remain neutral, equidistant. He is now in the antechamber of freedom. If “man becomes what he is”, then he became Nobody. Unruffled, fending off any sort of tropism, he has reabsorbed himself in a single impersonal face that contains all the others. He, the chained, the exalted the Duke d’Ivry, knows now a different drunkenness: that of silence and stillness, of contemplation, of gratuity, of the equivalence between being/not being. Against this background, the duke resembles Kagemusha – in the height of the battle, he remains still! That is all. The ceremonial battle dress which he is wearing in this triptych is like the sacred robe of liberation. The whole story is inscribed there, in the majestic triptych. Like a drop in the ocean, there is here also the story of the duke, with everything he is, wanted to be and had ever been, everything is woven there, his story and the story of those who are relating about him, together with the silences surrounding the story. Now there is nothing else to be said, apart from a ceremonious final sentence, preferably a quotation, a text in a text. The sentence we offer to view after prolonged textual arabesques and which we have kept up the sleeve so far so that the game doesn’t end too soon, makes the argument of a book on the “indubitable body” of writing, a body of delight, woven, seems to us now, from the threads of silk of the road to the East. Therefore, we have chosen the concluding sentence from Diana Adamek’s book Trupul neîndoielnicThe Unmistakable Body) to also end this text: “So, Scheherazade liked to tell the story of an emperor who believed that ‘even the most beautiful garden is yet another bookcase’.”