Erotikonia: imagini într-o abordare figurativă a temei, cu figuri simbolice, mitice, dintr-o viziune postmodernă, care îi pune în valoare în continuare artistului înclinația spre fabulos, spre imaginar, admirabilul simț compozițional, calitățile sale de mare colorist.

Dacă în literatură și muzică erosul a fost prezent încă din Antichitate și până astăzi, în artele plastice a fost mai dificil de tratat. Cât poți fi de explicit pentru a nu cădea în vulgaritate? Ioan Aurel Mureșan, așa cum a procedat în toate etapele sale de creație, recurge și acum la metafore, la simboluri, chiar la un realism magic. Curtezanele… femei care au tulburat și stimulat lumea masculină de-a lungul vremurilor. Phrine, iubita lui Praxiteles, a devenit încă o dată nemuritoare, oferind trupul său ca model de frumusețe și grație zeiței Afrodita din Cnid, sculptată de celebrul sculptor, fiind una dintre primele reprezentări la dimensiunea de corp viu a modelului feminin din sculptura greacă, în secolul al IV-lea. Libertățile de care se bucurau curtezanele din Antichitate ne fac să spunem că ele au fost primele femei libere. Multe erau inteligente, culte, nu numai frumoase, în casele lor având loc cenacluri, concursuri de poezie, se discuta filozofie. De altfel, filozofii și poeții au protestat împotriva condiției de inferioritate a femeilor, iar Socrate și Platon au susținut egalitatea naturală a celor două sexe.

Deci, o temă în care probleme de antropologie erotică se conjugă cu cele de sociologie, filozofie, psihologie, într-un complex de metamorfoze mentale și schimbări de optică. Nu cunosc în arta postmodernă din România o abordare de această amploare, aducând în prim-plan aspecte ale eroticului, cu accent pe latura sexual-senzuală a imaginarului erotic odată cu ieșirea în lumină a valorilor ce țin de corpul uman și de imaginarul plăcerii și al dorinței. Este o căutare (febrilă) a sensului și a locului erosului în viața cotidiană, a semnificațiilor ontologice, etice, estetice pe care acesta le instituie într-un imaginar polivalent. Conceptualizarea temei, investigarea ei într-o formulă diacronică, în comparație cu modelele deja consacrate, clasice, ale erosului, deplasările de accente, de interpretări originale într-o lume unde universul intim capătă o pondere tot mai mare și o autonomie tot mai pronunțată, se impune cu stringență.

Poetul Ioan Moldovan afirma la vernisajul expoziției că: „S-ar putea zice că pictorul îşi realizează conceptul cu deplină conformitate. Se întâmplă însă şi în acest caz acel fenomen miraculos în virtutea căruia opera nu se limitează la traseele intenţiei, ci îşi oferă propria sa aventură artistică, mult mai bogată în orizonturi şi reliefuri artistice decât programul prealabil, oricât ar fi acesta de subtil şi cuprinzător. Primul contact vizual cu lucrările lui I. A. Mureşan te sensibilizează şi, în acelaşi timp, te pune în gardă prin intensitatea cromatică. Ea corespunde unei viziuni plastice în ecuaţia căreia poeticile expresioniste, fauviste şi surealiste sunt asimilate de artist în chip profund şi original, caracteristicele fiecăreia nemaifuncţionând artificial şi artificios în actul de creaţie, ci la modul organic, firesc, încât trimiterile didactice la atari resurse ar fi fastidioase. (…)”.

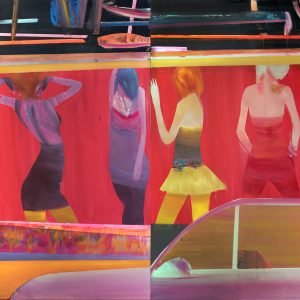

Ioan Aurel Mureșan are o atitudine mai curând constatatoare. El observă personajele, le urmărește curios, cu înțelegere, cu condescendență uneori, le dezvăluie seducția ce înseamnă ambiguitate și un joc al disimulării, pune sub semnul vizibilului ceva din viețile lor și, recurgând la „magic”, le salvează farmecul. Sunt curtezane într-un regat al roșului, al roșurilor care primesc valori nuanțate simbolic, mai ales roșu carmin, un roșu care arde până la carbonizare. Hetairele din tablourile lui Mureșan nu au aproape nimic de-a face cu anticele curtezane erudite. Sunt femei preocupate de trupul lor, de postură, deși au fețele ascunse ori sunt neindividualizate. Aparțin mai curând unei societăți consumiste, hedoniste, postmoderne, lăsând totul la vedere sau aproape totul. Lipsa de iluzii, de vise, de aspirații spre certitudini a transformat locul într-o lavă încinsă, de un roșu intens, care pare să curgă, ducând cu ea resturi, poate ființe topite, sugerând distructivul, haosul. Hetairele contemporane așteaptă, în poziții și mișcări provocatoare, pe consumatorii de eros fugar, iar o mașină tocmai s-a oprit, pentru a lua sau prelua o femeie-marfă. Fundalul de un roșu intens contribuie la sugerarea atmosferei de febrilă, de nerăbdătoare așteptare.

Lucrările sunt gândite pentru a exprima stări, dar mai ales situații, incluzând și pulsiuni refulate, mituri, arhetipuri, dar și reverii, vise prin forme simbolice, mitice, dar și prin forme care fac ca mesajul să fie unul tranșant. O deconstruire și reasamblare a toposurilor erotice tradiționale, pentru că semnificațiile imaginarului erotic propus de pictor se adresează timpului prezent, dar purtând o raportare la forme antice, ancestrale.

Escorte, curtezane, hetaire…, imagini vizuale ale „discursului” său despre erotic. Ioan Aurel Mureșan nu abordează erosul prin mitul androginului, povestit de Aristofan în Banchetul, a iubirii ca împlinire ontologică prin celălalt, ci din orizonturile unei postmodernități actuale, chiar contradictorii. El a preferat o exprimare în care a folosit o diversitate de „grile”, de la cea psihologică la cea psihanalitică, având dealtfel de-a lungul timpului o relație specială cu simbolicul și imaginarul.

Chiar dacă tema e evidentă, conceptul de erotism însumează o gamă largă de sensuri, imagini și simboluri fundamentale. Însăși tema presupune situarea erosului între iluzie și realitate, între așteptare, vag, împlinire ori neîmplinire, între interdicție și dorința de transgresiune a interdictului, creând tensiuni pe care le valorifică ontologic și cărora le conferă putere simbolică. Mureșan aduce în prim-plan corporalitatea în ficțiuni erotice în care rămâne important consumerismul și hedonismul. Sânii, coapsele, simboluri ale erosului, sunt măriți, figurile nu sunt individualizate, trăsăturile faciale sunt „șterse”, escortele nu au identitate proprie. Mișcările lente, pozițiile, atitudinile transmit stări, surprind momente ale existenței lor anonime.

În lucrarea Rosa canina, femeile sunt văzute parțial, dar în poziții sugestive, provocatoare. Apare ispita, iar flăcările fac totul scrum, sunt distrugătoare. Iubirile efemere, ademenitoare și promițătoare aduc eșecul, teama, așteptarea unui anume „ceva” mai autentic, care însă s-a transformat în ceva ce pare pierdut. În Avis amores, femeile cu forme planturoase, având alături păsări roșii cu valoare simbolică, cu chipurile ascunse așteaptă, privind spre formele cu înțeles erotic simbolic. Totul e așteptare, poate resemnare…

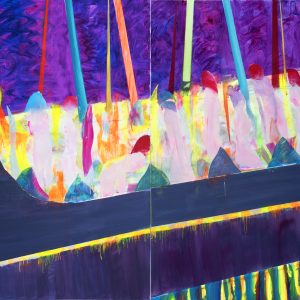

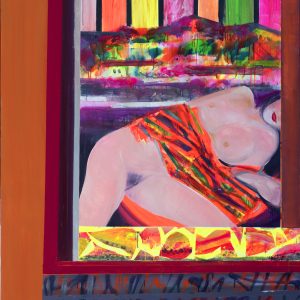

Divanul persan e adus în peisajul urban tentacular, cu blocurile înalte din ultimul plan. Tânăra femeie, aflată într-o poziție explicit erotică, privește formele cu aspecte masculine, statice, reci, cu ochii ascunși de ochelarii roșii, o lume primejdioasă, din care sentimentele tandre sunt excluse, iar iubirea inexistentă. Blocurile în roșu, lumea masculină în roșu-roz sunt amăgitoare, ascund pericolele inevitabile. Timpul trece… În centrul unui tablou (La belle jardiniere) apare o femeie nud — în atitudine de vampă, cu forme planturoase. Cadrul redă schematic o grădină, este atrăgător, dar femeia a trecut de prima tinerețe. Și totuși, încearcă încă să provoace. Cine nu și-ar dori să-și prelungească tinerețea, frumusețea? Mureșan a creat o parodie după Fântâna tinereții, pictată de Lucas Cranach. Fântâna are aspectul unei piscine înconjurate de forme rudimentare, ce amintesc de o năruire, iar apa e roșie, sugerând sacrificiul, bineînțeles și erosul. Femeile care se îmbăiază cu speranța de a fi iubite în continuare, văzute din spate, par ascunse în propriile lor vise neîmplinite. Au încă mișcări languroase, senzuale, deși tot ceea ce este în jurul lor e ruină. Iluziile vor pieri și ele. Șarpele este în lucrarea Mondragon simbol al erosului, de un roșu aprins. Trecerea lui sinuoasă transformă totul în lavă încinsă, periculoasă, de neoprit. Personajele feminine sunt neputincioase în fața lui, purtate în spații imaginare, topite sub dogoarea mișcărilor lui. Sub trecerea lui totul devine fluid până la curgere, descompus, dezagregat. Tușa e și ea lichefiată, vitalizată de roșul-lavă, de contrastele cromatice.

Fardul ca o sărbătoare e realitatea existenței escortelor. Ele trebuie să pară frumoase, să atragă consumatorul. Femei exotice în peisaje exotice, mișcări și atitudini ce au legătură cu profesia lor, aceea de a atrage, însoțite de animale ca simbol al erosului — iar roșul-flacără încinge și apoi va devora prada. De altfel, o lucrare se numește Camera magentă: personajul feminin e înconjurat de forme cu aluzii erotice, camera e pregătită, șarpele e prezent, aruncând flăcări mistuitoare. Patul a devenit lavă încinsă care topește corpul femeii. Roșul-magentă, intens, cel mai intens, a devenit devorator. Dar viața continuă. Cu forme planturoase, fanate, femeile își așteaptă în continuare căutătorii de plăceri ușoare, rapide. Par obosite, singure (Alte glasuri, alte încăperi).

Tablourile spun o poveste cu mijloace figurative, simbolice. Regatul roșului din aceste picturi este plin de primejdii, de drame. Iar mesajul? Fiecare privitor poate să aibă propria părere într-o lume marcată de dezordine. Corpul poate fi locul interior al libertății sale, o construcție simbolică și totodată suportul concepțiilor și practicilor unei epoci. Deci, corpul nu este accesibil într-o formă pură, ci doar în urma unor analize care conduc la perceperea lui într-un ansamblu cultural de civilizație. Trebuie observat că niciodată obsesia corpului nu a fost mai vie și mai puternică decât în perioada contemporană. Se poate vorbi despre dezvoltarea unui discurs creat în jurul expunerii infinite a corpului, susținut de o adevărată aviditate a privirii. Corpul poate fi considerat un vector esențial de expresie, un mediu privilegiat al artistului, devenind un „teritoriu vizual” (Carolee Schneeman). Efectul poate însemna însă confuzie, multiplicare… Deci, cu atât mai mult tema abordată de Ioan Aurel Mureșan este actuală, chiar dacă el doar o reprezintă pictural, dar cu înțelegerea artistului care a ajuns demult la maturitatea intelectuală și creatoare a unui magician al culorilor. O pictură figurativă într-o tratare sintetică, în care formele nonfigurative, abstracte contribuie la expresivitatea lucrărilor, cu forță poetică. O pictură care ne invită la meditație, la călătorii în adâncul nostru, în care mirajul nu lipsește nici de această dată. Cromatic, predomină roșul, într-o multitudine de nuanțe, cu semne mărunte, încărcate energetic, și în funcție de sensul imprimat imaginii apare și verdele, negrul, griurile colorate, griurile violacee, pasta fiind mai densă, tremurătoare, aspră, dar uneori și mătăsoasă, delicată. Ioan Aurel Mureșan este un magician al culorilor, care nu încetează să mă uimească prin felul în care exprimă, fără ostentație, cu mijloacele picturii, accesul la valorile infinite ale vieții, printr-o sugestivă acomodare a operei între figurativ și abstract. A pornit de la o idee post-modernă, dar imaginarul și implicit pictura și-a urmat drumul propriu, într-o călătorie în care, prin recurgerea la trupul feminin, a depășit primele intenții de abordare a eroticului. La fel ca în viață, drumul începe pentru a-și urma destinul, prin numeroase trasee, adeseori uluitoare, de unde nu lipsește fabulosul. Fascinantă această lume, mai ales datorită cromaticii, dar și simțului componistic coerent. Această amețitoare poveste, în care protagonist este nudul feminin, erosul, înseamnă până la urmă pictură, și putem afirma încă o dată că Ioan Aurel Mureșan este unul dintre marii pictori români contemporani.